Everything you think you know about diets is WRONG – The Diet Myth

by

EzekielDiet.com

by

EzekielDiet.comPosted on May 12, 2015

Counting calories is a total waste of time, it’s bacteria in your gut that make you fat and finally, cheese, alcohol and chocolate can all help

Professor Tim Spector, a leading genetics expert, finds compelling evidence as to why calorie-controlled diets don’t work

He believes with the right regimen of diet and exercise, we can be happy, healthy – and lean – and keep the pounds off for life

Author of new book The Diet Myth: The Real Science Behind What We Eat

Calorie-controlled diets don’t work.

Many of us may have suspected as much for years — but now there’s compelling evidence in a new book by Professor Tim Spector, a leading genetics expert at King’s College London.

What’s more, he’s offering a tantalizing new theory about what really makes us fat — which could revolutionize our approach to weight loss.

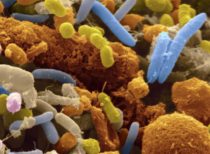

As one of the scientists leading worldwide research into the trillions of bacteria living in our stomachs, Professor Spector believes they hold an amazing power over our health and moods — and that our modern diet may be having a negative effect on them.

His specialist area is twins. For more than two decades, he has been scientifically following 11,000 identical twins, examining information on their health, lifestyles and diet habits to discover the role of environmental and genetic factors in disease.

And one of his key findings will come as a shock to anyone who puts their faith in calorie-controlled dieting and the idea that the current obesity epidemic is simply down to people taking in more calories, and burning fewer through exercise, than previous generations did.

In fact, suggests Professor Spector, if you put identical twins on high-calorie diets, where they eat an extra 1,000 calories every day, after six weeks they’ll have completely different changes in weight.

Some will have gained as much as 13 kg, others as little as 4 kg — all on identical diets.

Clearly, calories aren’t the only factor. So what’s going on?

Professor Spector believes it’s down to the bacteria in our gut. He has found that the type and variety of our gut bugs have an astonishing influence on many aspects of our health.

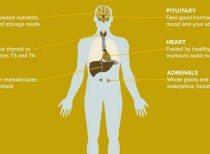

‘Microbes are not only essential to how we digest food,’ he says.

‘They also control the calories we absorb and provide vital enzymes and vitamins, as well as keeping our immune system healthy.’

Our gut microbes are also linked to cardiovascular health, risk of diabetes and mental wellbeing.

In a book published this week, The Diet Myth: The Real Science Behind What We Eat, Professor Spector argues that, with the right regimen of diet and exercise, we can change our personal mix of gut bacteria to become one that keeps us happy, healthy — and lean.

For he also believes bacteria are likely to be responsible for much of our obesity epidemic. The root of the problem, he says, may be our modern diet and its effect on our gut bugs.

Compared with our ancestors, we have only a fraction of the diversity of microbial species living in our guts.

Fifteen thousand years ago, man regularly ate around 150 ingredients in a week.

Nowadays, most people consume fewer than 20 separate food items, and many — if not most — of these are artificially refined, says Professor Spector.

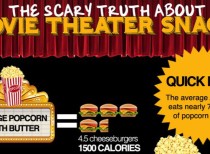

To test what a modern-day junk food diet does to our gut bacteria, he enlisted the help of his 22-year-old son, Tom.

For ten days, Tom, a student, went on a diet exclusively of Chicken McNuggets and Big Macs, washed down with McFlurry ice cream desserts and regular Cokes.

By the sixth day, he reported feeling bloated and sluggish. On the eighth, he’d started to sweat after the meals.

‘Tom found that his [university] assignments took even longer than usual,’ says Professor Spector. ‘Friends remarked that his skin seemed to have a yellow tinge and he looked unwell.’

Hardly surprisingly, by the end of the experiment, Tom had put on 4 lb. But what was telling were the results of the tests on his gut bacteria, which found that just three days in, 40 per cent of the bugs had died.

Bad bacteria thrive on a junk food diet

The bacteria that remained in Tom’s gut showed a worrying profile.

Levels of health-promoting bugs had plummeted, while dangerous bacteria had thrived.

Tom’s levels of firmicutes, for example — which create chemicals that fuel our cells with sugars, fatty acids, proteins and vitamins, enabling the body’s myriad systems to communicate with one other properly — had halved.

Meanwhile, he had higher levels of bacteria associated with inflammation, which is linked to cancer and heart disease, and with damage to the immune system.

Professor Spector found that several rare bacteria species flourished on the diet, including one called Lautropia. This, he explains, is ‘usually only noticed in immune-deficient patients’.

Tom’s mix of gut bugs was still unhealthy a week later but, thankfully, slowly began to return to normal after he began eating properly again.

But what about the weight he’d gained?

Nowadays, we naturally associate junk food diets with weight gain. But is it the food itself that causes the pounds to pile on — or could it be a result of the damage it causes to our diversity of gut bacteria?

To find out, Professor Spector, who is head of the Department of Twin Research and Genetic Epidemiology at St Thomas’ Hospital, London, turned to his area of expertise.

Identical twins are particularly useful because they are genetically identical — which means any differences in, for example, their weight must be a result of their lifestyle and environment.

Professor Spector’s work has revealed a number of significant findings in relation to bacteria.

A study of four pairs of twins where one was obese and the other was not found notable differences between their gut microbes — with the leaner twin in each pair ‘having a richer and healthier set, and the fatter twin having a less diverse, inflammatory-looking profile’.

Stool samples were then taken from the twins and transplanted into the guts of mice. ‘The results were surprisingly clear-cut,’ says Professor Spector. ‘The mice receiving the fat twins’ stool samples quickly became 16 per cent fatter.

‘This was clear proof that fat-associated microbes are really toxic and can be transmitted like an infection. The toxic microbes are more likely to grow rapidly in our guts and be a problem if other microbes are suppressed or if there is a lack of diversity.’

Naturally slim? Thank your gut!

If toxic gut bugs can make us fat, could beneficial bugs have the opposite effect?

Professor Spector’s team experimented with a microbe called Christensenella, which is associated with being lean.

When they transplanted it into mice, it prevented them getting fat — despite their being on high-fat diets. While this works well on lab mice, in humans the answer is not as simple as just giving Christensenella to everyone. Other factors complicate matters significantly, such as the mix of bugs already in individual people’s stomachs (the mice’s guts were germ-free before the experiments), and the question of whether a person’s individual genes are friendly to Christensenella.

‘Some humans who have this microbe appear to be protected against obesity but, unfortunately, many do not,’ says Professor Spector, who recently founded the British Gut Project, which aims to identify the ‘bacterial diversity’ of the British gut and how it affects our health.

Professor Spector is convinced by his twin studies that changing our gut bugs offers a surer and safer way of staying lean than going on calorie-controlled diets.

That’s because other studies he’s done with twins have suggested standard dieting just won’t work.

‘You might have predicted that a twin who had the willpower to diet regularly would have something to show for their years of sacrifice,’ he says.

‘Instead, I found no difference in weight between a twin who had dieted regularly for the past 20 years and her identical twin who had never been on a serious diet.’

Even more dismal results were found in pairs of younger twins who were the same weight at the age of 16. When the pairs were compared at the age of 25, the twin who had dieted was, on average, 1.5 kg heavier.

Professor Spector believes one of the reasons why is that our bodies have evolved to resist times of famine by holding onto their stores of fat.

Dieting can also be dangerous, he adds. ‘The increasing promotion and use of restrictive diets that depend on just a few ingredients will inevitably lead to a further reduction in microbe diversity and, eventually, to ill-health.’

Understanding how these myriad microbes act and interact with each other and our genes is still in its infancy.

Before we can be prescribed with personalised gut-friendly diets, scientists need to unravel the extremely complex puzzles that make individuals respond differently to the same diets.

In the meantime, though, science has already discovered a range of ways in which we can all healthily improve the number and diversity of our gut bacteria — and help to keep a plague of modern illness epidemics at bay.

Be good to your gut — do more exercise

Exercise alone doesn’t lead to significant weight loss, argues Professor Spector. Research also shows it won’t help keep it off.

However, it is good for your heart and brain — and your gut bacteria.

Results from the professor’s studies of 3,000 twins show that the amount of exercise they took is the strongest factor in promoting the richness of their gut microbes.

The findings are supported by a study of elite athletes in the national Irish rugby squad, published last year in the journal Gut.

Nutritionists at University College Cork found that the athletes had much more diverse stomach bacteria than normal, as well as lower levels of inflammation.

So, how does exercise have this effect? One way in which it does this is by stimulating the immune system, which, in turn, sends stimulating chemical signals to the microbes in our guts, according to a 2011 study in the journal Immunology Investigations.

Exercise also benefits our balance of gut bugs directly, according to a 2008 report in the journal Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry.

The study of lab rats showed that those exercising on a wheel produced twice as much of the fatty acid butyrate in their guts compared with sedentary rats.

Butyrate is produced by our gut microbes and has a broad range of beneficial effects on the immune system, says the report. Exercise stimulates microbes to produce more of it.

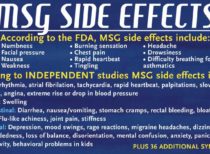

Artificial sweeteners should be avoided

When researchers fed rats artificial sweeteners at the recommended human doses for three months, they found that their levels of bacteria and diversity dropped significantly.

And this particularly harmed the health-enhancing microbes, according to a 2008 study in the Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health.

Tests on mice by Israeli researchers suggested that artificial sweeteners can alter the balance of gut bacteria, so that the bugs, in turn, release chemicals that, ironically, raise blood sugar levels, increasing the risk of weight gain and diabetes.

But chocolate’s fine… as long as it’s dark

When participants in a study at the University of Reading were given cocoa extracts for four weeks, their levels of beneficial stomach bacteria rose significantly.

Meanwhile, levels of potentially harmful bugs and bodily inflammation fell, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition reported in 2011.

It seems microbes enjoy chocolate as much as we do. In the gut, they play a major role turning chemicals from cocoa into substances that lower the level of potentially harmful fat and ‘bad’ LDL cholesterol in our bloodstream.

To get the benefits without piling on the pounds, the darker the chocolate, the better.

Milk chocolate contains only one-fifth of the cocoa of dark chocolate, so you would have to eat five times as much to get the same bacterial benefits — which would mean a lot more sugar and fat, too.

The Diet Myth: The Real Science Behind What We Eat is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson on May 14.

The British Gut Project is looking for more people to sign up to join its sample project — to have your gut population identified (for a cost of around £75), go to britishgut.org.

Professor Tim Spector will hold a Twitter Q&A on Wednesday, May 20, at 12:30pm. Send questions to @timspector using #asktimspector

Featured Videos

MORE ARTICLES

-

Greg Reese: Artificial Intelligence and the Grim Future of a Divided Humanity

Greg Reese: Artificial Intelligence and the Grim Future of a Divided Humanity

Apr 24,2024 10:58 am

-

From the Fringe: Caster Oil Treatment on Skin and Warts

From the Fringe: Caster Oil Treatment on Skin and Warts

Apr 24,2024 10:20 am

-

Dr. Bryan Ardis: Detox – How to use Nicotine – Patches and Gum

Dr. Bryan Ardis: Detox – How to use Nicotine – Patches and Gum

Apr 24,2024 9:43 am

-

Why You Don’t Want a WordPress Website & Subscription Software – Pay Once & Own It

Why You Don’t Want a WordPress Website & Subscription Software – Pay Once & Own It

Apr 23,2024 10:03 am

-

Put a Missionary on the Payroll Spotlight: Bob & Beth Xavier – Things To Come Mission

Put a Missionary on the Payroll Spotlight: Bob & Beth Xavier – Things To Come Mission

Apr 21,2024 5:35 pm

-

Remember Kathy Griffin’s Trump Head Incident? Check Out Her New Head Today…

Remember Kathy Griffin’s Trump Head Incident? Check Out Her New Head Today…

Apr 21,2024 3:42 pm

-

Transhumanist Plan To Exterminate All Humans Now Public Information

Transhumanist Plan To Exterminate All Humans Now Public Information

Apr 21,2024 12:58 pm

-

DR. BRYAN ARDIS | What you Don’t Know about Nicotine could KILL YOU! Exposing the Lie. Revealing the Benefits.

DR. BRYAN ARDIS | What you Don’t Know about Nicotine could KILL YOU! Exposing the Lie. Revealing the Benefits.

Apr 20,2024 6:01 pm

-

From the Fringe: The Laundry Detergent Conspiracy

From the Fringe: The Laundry Detergent Conspiracy

Apr 19,2024 9:45 pm

-

WARNING: WHO Plans Global Coup of 194 UN Member Nations. International Wakeup Call

WARNING: WHO Plans Global Coup of 194 UN Member Nations. International Wakeup Call

Apr 19,2024 4:59 pm

-

Tucker Carlson Interviews Pastor Doug Wilson In Defense of Christian Nationalism

Tucker Carlson Interviews Pastor Doug Wilson In Defense of Christian Nationalism

Apr 19,2024 4:23 pm

-

Humans Being Turned Into Batteries To Fuel Digital A.I. Prison

Humans Being Turned Into Batteries To Fuel Digital A.I. Prison

Apr 18,2024 4:35 pm

-

X-Files predictive programming: Vaccines, Depopulation, EMP, Collapse, Invassion

X-Files predictive programming: Vaccines, Depopulation, EMP, Collapse, Invassion

Apr 18,2024 9:25 am

-

Magnesium – The Weight Loss Cure – Dr. Carolyn Dean

Magnesium – The Weight Loss Cure – Dr. Carolyn Dean

Apr 18,2024 7:20 am

-

Supplements I Take Daily

Supplements I Take Daily

Apr 17,2024 10:43 am

-

Food for the brain: Review examines the link between diet and mental health

Food for the brain: Review examines the link between diet and mental health

Apr 17,2024 8:49 am

-

Update to Perricone MD’s Top 10 Supplements for Healthy, Beautiful Aging & Living

Update to Perricone MD’s Top 10 Supplements for Healthy, Beautiful Aging & Living

Apr 17,2024 8:44 am

-

From the Fringe: The Most Important News – Michael Snyder Daily Feed

From the Fringe: The Most Important News – Michael Snyder Daily Feed

Apr 17,2024 8:32 am

-

Dr. Paul Craig Roberts Institute for Political Economy – Daily Feed

Dr. Paul Craig Roberts Institute for Political Economy – Daily Feed

Apr 17,2024 8:15 am

-

CLA: The experts speak on Conjugated Linoleic Acid and weight loss

CLA: The experts speak on Conjugated Linoleic Acid and weight loss

Apr 17,2024 7:12 am

-

299 out of 300 Iranian Drones Shot Down? Really? Did you see them?

299 out of 300 Iranian Drones Shot Down? Really? Did you see them?

Apr 15,2024 9:18 am

-

Put a Missionary on the Payroll Spotlight: Asuncion “Ciony” Buca – Things To Come Mission

Put a Missionary on the Payroll Spotlight: Asuncion “Ciony” Buca – Things To Come Mission

Apr 14,2024 6:06 pm

-

Universal Commercial Code. A Systematic Enslavement. How to Free Yourself from Legal Tyranny

Universal Commercial Code. A Systematic Enslavement. How to Free Yourself from Legal Tyranny

Apr 14,2024 9:01 am

-

From the Fringe: Not The Moon Causing the Solar Eclipse

From the Fringe: Not The Moon Causing the Solar Eclipse

Apr 11,2024 9:13 am

-

Lies About The Sun and Moon – You Live in a Matrix of Lies; Question Everything.

Lies About The Sun and Moon – You Live in a Matrix of Lies; Question Everything.

Apr 10,2024 10:03 am

-

From the Eclipse: Donald Trump Shares Bizarre Eclipse Campaign Alert

From the Eclipse: Donald Trump Shares Bizarre Eclipse Campaign Alert

Apr 09,2024 2:30 pm

-

Put a Missionary on the Payroll Spotlight: Aaron & Noemi Arsino – Things To Come Mission

Put a Missionary on the Payroll Spotlight: Aaron & Noemi Arsino – Things To Come Mission

Apr 08,2024 12:52 pm

-

Reese Report: A.I. Deciding Who To Kill For Israel

Reese Report: A.I. Deciding Who To Kill For Israel

Apr 05,2024 8:58 pm

-

525 Hogs mRNA Vaccinated – 30% Dead or Near Death – Autopsy Found Live mRNA in the Meat

525 Hogs mRNA Vaccinated – 30% Dead or Near Death – Autopsy Found Live mRNA in the Meat

Apr 05,2024 5:18 pm

-

From the Fringe: Summoning Evil Entities at CERN, Solar Eclipse & More

From the Fringe: Summoning Evil Entities at CERN, Solar Eclipse & More

Apr 04,2024 7:29 pm

-

Reese Report: Major Events Surrounding the April 8th Solar Eclipse

Reese Report: Major Events Surrounding the April 8th Solar Eclipse

Apr 04,2024 3:15 pm

-

This Is Why Many People Will Consider The Great American Eclipse Of 2024 On April 8th To Be A Big “Dud”

This Is Why Many People Will Consider The Great American Eclipse Of 2024 On April 8th To Be A Big “Dud”

Apr 03,2024 10:30 am

-

Private Member Associations (PMA’s) and Non-Taxable Trusts– MARK ATTWOOD

Private Member Associations (PMA’s) and Non-Taxable Trusts– MARK ATTWOOD

Apr 03,2024 9:14 am

-

What Happened The Last Time Two Eclipses Formed A Giant “X” Over The New Madrid Fault Zone?

What Happened The Last Time Two Eclipses Formed A Giant “X” Over The New Madrid Fault Zone?

Apr 02,2024 9:43 am

-

From the Fringe: Nuclear Poppycock, Atomic Balderdash, Fear & Stagecraft

From the Fringe: Nuclear Poppycock, Atomic Balderdash, Fear & Stagecraft

Apr 01,2024 7:14 pm

-

Bought, Purchased, Redeemed and Ransomed. Is the Shroud of Turin “The Receipt Of The Resurrection of Jesus”?

Bought, Purchased, Redeemed and Ransomed. Is the Shroud of Turin “The Receipt Of The Resurrection of Jesus”?

Mar 31,2024 10:33 am

-

Movie: Risen (2016) – He Is Everywhere Scene – On YouTube & Prime

Movie: Risen (2016) – He Is Everywhere Scene – On YouTube & Prime

Mar 31,2024 9:40 am

-

These Miraculous Events Prove the Perfect Unity of the Trinity

These Miraculous Events Prove the Perfect Unity of the Trinity

Mar 31,2024 8:31 am

-

Two Hour Slow Cooker Apple Crisp for a Day

Two Hour Slow Cooker Apple Crisp for a Day

Mar 27,2024 5:52 pm

-

Why Glycine is Important in 2024 – Glutathione – Detox – Weight Loss – Liver Cleanse – Collagen – Visceral Fat – Hair Loss

Why Glycine is Important in 2024 – Glutathione – Detox – Weight Loss – Liver Cleanse – Collagen – Visceral Fat – Hair Loss

Mar 27,2024 4:08 pm

-

Michael McKibben’s newest invention – MySQIF. YES. TRUE PRIVACY IS HERE

Michael McKibben’s newest invention – MySQIF. YES. TRUE PRIVACY IS HERE

Mar 27,2024 7:36 am

-

Movie Nefarious – Demon Explains To Atheist Doctor Their Plan Against Humanity

Movie Nefarious – Demon Explains To Atheist Doctor Their Plan Against Humanity

Mar 26,2024 8:58 am

-

Operation Gladio: The Unholy Alliance Between the Vatican, the CIA, and the Mafia (Full Audiobook)

Operation Gladio: The Unholy Alliance Between the Vatican, the CIA, and the Mafia (Full Audiobook)

Mar 25,2024 9:46 am

-

Greg Reese: The British Royals and the Reptilians

Greg Reese: The British Royals and the Reptilians

Mar 22,2024 9:04 pm

-

News With Views – Where Reality Shatters Illusion – Daily Feed

News With Views – Where Reality Shatters Illusion – Daily Feed

Mar 22,2024 8:15 am

-

Diet Science Weekly Feed – Four Fats That Burn Body Fat

Diet Science Weekly Feed – Four Fats That Burn Body Fat

Mar 22,2024 7:57 am

-

Skywatch TV Podcast Daily Feed

Skywatch TV Podcast Daily Feed

Mar 22,2024 6:58 am

-

Outside Your Birdcage: MOST IMPORTANT Lessons Americans Were Never Taught in School

Outside Your Birdcage: MOST IMPORTANT Lessons Americans Were Never Taught in School

Mar 20,2024 10:55 am

-

Silent Frequencies: Exposing the Covert World of Mind Control in Media – Veritas

Silent Frequencies: Exposing the Covert World of Mind Control in Media – Veritas

Mar 19,2024 8:03 am

-

Outside the Birdcage: Parasitic Science and the Unproven Virus | Greg Reese

Outside the Birdcage: Parasitic Science and the Unproven Virus | Greg Reese

Mar 14,2024 10:27 am

-

V.A.I.D.S. Vaccine Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome – The Multi Shot Process

V.A.I.D.S. Vaccine Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome – The Multi Shot Process

Mar 14,2024 9:31 am

-

Rogan: Ray Kurzweil – AI in 2029 – The Singularity Is Nearer with Google Bucks

Rogan: Ray Kurzweil – AI in 2029 – The Singularity Is Nearer with Google Bucks

Mar 13,2024 7:36 am

-

Chris Pinto – The Vatican’s Immigration War – Noise of Thunder Radio

Chris Pinto – The Vatican’s Immigration War – Noise of Thunder Radio

Mar 09,2024 12:11 pm

-

Fighting for health freedom against government tyranny: XLEAR company founder Nathan Jones

Fighting for health freedom against government tyranny: XLEAR company founder Nathan Jones

Mar 08,2024 3:34 pm

-

Florida Supreme Court To Seize CLOT SHOTS? High Court To Halt BIOWEAPON

Florida Supreme Court To Seize CLOT SHOTS? High Court To Halt BIOWEAPON

Mar 08,2024 9:05 am

-

Top Oncologist Blows Whistle on mRNA Fallout: ‘We’ve Never Seen Cancers Behave Like This’

Top Oncologist Blows Whistle on mRNA Fallout: ‘We’ve Never Seen Cancers Behave Like This’

Mar 07,2024 2:49 pm

-

Secret Ukrainian Agenda: Greater Israel Jewish State

Secret Ukrainian Agenda: Greater Israel Jewish State

Mar 05,2024 1:08 pm

-

Mel Gibson: Global Elites Will Keep Dying To Make Way For The Antichrist

Mel Gibson: Global Elites Will Keep Dying To Make Way For The Antichrist

Mar 05,2024 11:00 am

-

Curse of Canaan’s War on the White Race Programmed into Google’s Gemini AI

Curse of Canaan’s War on the White Race Programmed into Google’s Gemini AI

Mar 03,2024 2:30 pm

-

Outside the Birdcage: Compilation of Vax Pushing Influencers Documenting Their Deaths For Clicks

Outside the Birdcage: Compilation of Vax Pushing Influencers Documenting Their Deaths For Clicks

Feb 27,2024 3:03 pm

-

Launching the religious cult meme? Going after the “white christian nationalists”

Launching the religious cult meme? Going after the “white christian nationalists”

Feb 26,2024 12:26 pm

-

The Kalergi Plan – The Curse of Canaan – The History of War Against the White Race

The Kalergi Plan – The Curse of Canaan – The History of War Against the White Race

Feb 23,2024 9:30 am

-

WARNING: What is Neuralink Really For? The Privacy Guy 2-14-2024

WARNING: What is Neuralink Really For? The Privacy Guy 2-14-2024

Feb 19,2024 10:25 am

-

Greg Reese: Hydrogels in COVID Vaccine as Programmable Human Interface

Greg Reese: Hydrogels in COVID Vaccine as Programmable Human Interface

Feb 18,2024 11:55 am

-

From the Fringe: The Miracles of Castor Oil

From the Fringe: The Miracles of Castor Oil

Feb 15,2024 8:42 am

-

Rogan: Why Bret Weinstein is Concerned About the Migrant Crisis

Rogan: Why Bret Weinstein is Concerned About the Migrant Crisis

Feb 15,2024 12:28 am

-

Tucker Carlson & Dr. Joseph Ladapo: Covid-19 Vaccines are the Antichrist of all Products

Tucker Carlson & Dr. Joseph Ladapo: Covid-19 Vaccines are the Antichrist of all Products

Feb 14,2024 11:20 pm

-

The Weaponization of Illegal Immigrant Invasions Used To Destroy America From Within

The Weaponization of Illegal Immigrant Invasions Used To Destroy America From Within

Feb 13,2024 9:08 am

-

Texe Marrs – Kabbalah is the Secret Foundation of Many False Religions

Texe Marrs – Kabbalah is the Secret Foundation of Many False Religions

Feb 09,2024 6:17 pm

-

Reese Report: 30 Years of Russia Seeking Peace with the West

Reese Report: 30 Years of Russia Seeking Peace with the West

Feb 09,2024 4:33 pm

-

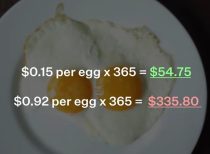

Are Expensive Eggs actually worth it?

Are Expensive Eggs actually worth it?

Feb 08,2024 9:49 am

-

The World is a Much Brighter Place When You’re Not Too Bright For It – Satire – IQ Lowering Pill

The World is a Much Brighter Place When You’re Not Too Bright For It – Satire – IQ Lowering Pill

Feb 02,2024 1:07 pm

-

From the Fringe: Ron Wyatt Discoveries – 2022 Documentary

From the Fringe: Ron Wyatt Discoveries – 2022 Documentary

Jan 31,2024 2:03 pm

-

Greg Reese: Underground Tunnels and Hybrid Breeding Programs

Greg Reese: Underground Tunnels and Hybrid Breeding Programs

Jan 27,2024 6:36 pm

-

Are Dr. Berg & Bobby Perrish right about meat & seafood at Costco?

Are Dr. Berg & Bobby Perrish right about meat & seafood at Costco?

Jan 24,2024 3:44 pm

-

Outside the Birdcage: The Invasion Of Gog (Rothschild) And Magog (Khazar Jews)

Outside the Birdcage: The Invasion Of Gog (Rothschild) And Magog (Khazar Jews)

Jan 21,2024 12:17 pm

-

Great Theologians of the 16th to 20th Centuries on Revelation and Historicism

Great Theologians of the 16th to 20th Centuries on Revelation and Historicism

Jan 14,2024 11:41 am

-

Outside the Birdcage: All The World Is A Stage – It’s Time To Wake Up

Outside the Birdcage: All The World Is A Stage – It’s Time To Wake Up

Jan 10,2024 1:36 pm

-

Outside the Birdcage: The Takeover and Secret Destiny of the USA

Outside the Birdcage: The Takeover and Secret Destiny of the USA

Jan 08,2024 2:29 pm

-

UN SDG 13: Climate Action Will Destroy Your Life and Modern Industrial Civilization

UN SDG 13: Climate Action Will Destroy Your Life and Modern Industrial Civilization

Jan 06,2024 6:57 pm

-

From the Fringe: Government is Preparing for Covid Vaxxed Zombies?

From the Fringe: Government is Preparing for Covid Vaxxed Zombies?

Jan 05,2024 7:57 pm

-

Home & Appliance Repair Cost Out-of-Control in America – Business Idea

Home & Appliance Repair Cost Out-of-Control in America – Business Idea

Jan 05,2024 10:46 am

-

SkywatchTV Latest News Daily Feed

SkywatchTV Latest News Daily Feed

Jan 02,2024 8:00 am

-

From the Fringe: Eustace Mullins – Murder by Injection (Full Length)

From the Fringe: Eustace Mullins – Murder by Injection (Full Length)

Jan 02,2024 7:35 am

-

Outside the Birdcage: Revelation Timeline Decoded Bible Study Guide – David Nikao Wilcoxson

Outside the Birdcage: Revelation Timeline Decoded Bible Study Guide – David Nikao Wilcoxson

Dec 31,2023 12:38 pm

-

From the Fringe: Some Pixies show up in the woods? Hoax?

From the Fringe: Some Pixies show up in the woods? Hoax?

Dec 29,2023 3:02 pm

-

From the Fringe: Why Some Drop Dead and Others Don’t – Payload Spill

From the Fringe: Why Some Drop Dead and Others Don’t – Payload Spill

Dec 26,2023 2:13 pm

-

Poison in Your Food: Milk. It Does a Body Bad

Poison in Your Food: Milk. It Does a Body Bad

Dec 26,2023 1:25 pm

-

From the Fringe: Broadcast MAC Address Detected in Vial of Blood

From the Fringe: Broadcast MAC Address Detected in Vial of Blood

Dec 26,2023 10:22 am

-

Outside the Birdcage: Myths About the Birth of Christ (Luke 2:1-11)

Outside the Birdcage: Myths About the Birth of Christ (Luke 2:1-11)

Dec 24,2023 3:44 pm

-

From the Fringe: Dangers within Preterism – Pt 1 & Pt 2

From the Fringe: Dangers within Preterism – Pt 1 & Pt 2

Dec 24,2023 7:43 am

-

Outside the Birdcage: Christians Supporting Israel Are Wrong

Outside the Birdcage: Christians Supporting Israel Are Wrong

Dec 23,2023 9:40 am

-

Compelling Historical Evidence for the Virgin Birth of Jesus Christ

Compelling Historical Evidence for the Virgin Birth of Jesus Christ

Dec 22,2023 8:00 am

-

7 Easy Ways to Avoid Holiday Weight Gain – And Have a Great Time Doing It

7 Easy Ways to Avoid Holiday Weight Gain – And Have a Great Time Doing It

Dec 22,2023 7:31 am

-

Caution: Holiday Health Hazards Ahead!

Caution: Holiday Health Hazards Ahead!

Dec 22,2023 7:00 am

-

How December 25 Became Christmas

How December 25 Became Christmas

Dec 22,2023 7:00 am

-

The Curse of Canaan: A Demonology of History, by Eustace Mullins. Audiobook Full

The Curse of Canaan: A Demonology of History, by Eustace Mullins. Audiobook Full

Dec 20,2023 10:10 am

-

Inside the Birdcage: New Civil War Movie

Inside the Birdcage: New Civil War Movie

Dec 18,2023 12:35 pm

-

Outside the Birdcage: Machiavelli – The Art of Power in The Modern World.

Outside the Birdcage: Machiavelli – The Art of Power in The Modern World.

Dec 18,2023 10:52 am

-

First World Leader Facing Murder Charges For Pushing mRNA Vaccines on Public

First World Leader Facing Murder Charges For Pushing mRNA Vaccines on Public

Dec 18,2023 9:29 am

-

From the Fringe & Outside the Birdcage: The Olive Tree & True Israel (Romans 11:16-18)

From the Fringe & Outside the Birdcage: The Olive Tree & True Israel (Romans 11:16-18)

Dec 15,2023 12:58 pm

-

Outside the Birdcage – Tavis tock In stitute of Mind Con trol Exposed

Outside the Birdcage – Tavis tock In stitute of Mind Con trol Exposed

Dec 14,2023 2:38 pm

-

Outside the Birdcage: The Secret Dark Origins of Christmas

Outside the Birdcage: The Secret Dark Origins of Christmas

Dec 11,2023 9:25 am

-

Owew Shroyer RETURNS!

Owew Shroyer RETURNS!

Dec 10,2023 3:06 pm

-

From the Fringe: No Jewish Race Today? – Modern Israel & Biblical Jews

From the Fringe: No Jewish Race Today? – Modern Israel & Biblical Jews

Dec 09,2023 8:35 am

-

NETFLIX IS NOT WHAT YOU THINK IT IS!

NETFLIX IS NOT WHAT YOU THINK IT IS!

Dec 06,2023 2:24 pm

-

Revelation part 2 Preterist Idealist View (Rev. 1:1-3)

Revelation part 2 Preterist Idealist View (Rev. 1:1-3)

Dec 03,2023 1:30 pm

-

From the Fringe: Who Placed The Beatles on the World Stage and Why?

From the Fringe: Who Placed The Beatles on the World Stage and Why?

Dec 01,2023 12:42 pm

-

The Perfect Human Diet – Exploring the obesity epidemic – FULL DOCUMENTARY

The Perfect Human Diet – Exploring the obesity epidemic – FULL DOCUMENTARY

Nov 30,2023 12:53 pm

-

From the Fringe: The Secret Founding of America

From the Fringe: The Secret Founding of America

Nov 29,2023 1:39 pm

-

From the Fringe: Christians and Israel Today? (Romans 9:6)

From the Fringe: Christians and Israel Today? (Romans 9:6)

Nov 29,2023 9:22 am

-

From the Fringe: What’s Going On In Israel Has Nothing To Do With Bible Prophecy or Last Days

From the Fringe: What’s Going On In Israel Has Nothing To Do With Bible Prophecy or Last Days

Nov 28,2023 8:44 am

-

From the Fringe: Revelation part 1 Preterist View (Rev 1:1)

From the Fringe: Revelation part 1 Preterist View (Rev 1:1)

Nov 26,2023 1:08 pm

-

Rush Limbaugh 2010: Socialism Nearly Killed The Pilgrims

Rush Limbaugh 2010: Socialism Nearly Killed The Pilgrims

Nov 24,2023 3:51 pm

-

Sweet potatoes can support digestive health and protect against cancer

Sweet potatoes can support digestive health and protect against cancer

Nov 24,2023 3:20 pm

-

What Was It Really Like Aboard The Mayflower – Journey Into Unknown

What Was It Really Like Aboard The Mayflower – Journey Into Unknown

Nov 23,2023 12:42 pm

-

The Origin of Thanksgiving Foods & Today’s Lab Coat GMO Bigger Better Tastier Versions

The Origin of Thanksgiving Foods & Today’s Lab Coat GMO Bigger Better Tastier Versions

Nov 21,2023 10:00 am

-

You Become What You Think About – Controlling Your Mind in Troubled Times

You Become What You Think About – Controlling Your Mind in Troubled Times

Nov 20,2023 1:48 pm

-

From the Fringe: A Message to Humanity… Game Over

From the Fringe: A Message to Humanity… Game Over

Nov 18,2023 10:18 am

-

Grapefruit found to help reduce high blood pressure

Grapefruit found to help reduce high blood pressure

Nov 17,2023 7:46 am

-

Stew Peters with Bonus after show chat – Flat Earth discussion

Stew Peters with Bonus after show chat – Flat Earth discussion

Nov 16,2023 9:10 am

-

Dr. Lorraine Day passed away on November 10, 2023

Dr. Lorraine Day passed away on November 10, 2023

Nov 15,2023 6:53 pm

-

Dr. John Campbell: Excess deaths in 2023

Dr. John Campbell: Excess deaths in 2023

Nov 15,2023 5:32 pm

-

The Deliberate Destruction of America – Dr. Lorraine Day

The Deliberate Destruction of America – Dr. Lorraine Day

Nov 15,2023 8:36 am

-

From the Fringe: The Battle for Your Mind

From the Fringe: The Battle for Your Mind

Nov 14,2023 11:35 am

-

Dr. Bryan Ardis | 3 Tips for Maintaining Gut Health – Flyover Clips

Dr. Bryan Ardis | 3 Tips for Maintaining Gut Health – Flyover Clips

Nov 12,2023 10:41 am

-

Walter Veith – Sun Tzu, The Jesuits, America and The Art of War

Walter Veith – Sun Tzu, The Jesuits, America and The Art of War

Nov 05,2023 8:16 am

-

Elaborate Hoax or Real Vanishing People Caught on Camera?

Elaborate Hoax or Real Vanishing People Caught on Camera?

Nov 03,2023 9:32 am

-

01:34 Short Video: Ingested Pesticide Levels in Urine Before and After an Organic Diet

01:34 Short Video: Ingested Pesticide Levels in Urine Before and After an Organic Diet

Oct 31,2023 7:46 am

-

FAT 101 – How the food industry is deceiving you – Peter Jennings ABC – Must See

FAT 101 – How the food industry is deceiving you – Peter Jennings ABC – Must See

Oct 30,2023 7:00 am

-

The Subtle Boardroom Scene Message in the 1976 movie Network

The Subtle Boardroom Scene Message in the 1976 movie Network

Oct 28,2023 7:00 am

-

The War on Wheat – the fifth estate

The War on Wheat – the fifth estate

Oct 27,2023 8:19 am

-

How Smoothly Is Your Life Rolling Along? The Wheel of Life Can Change Your Life

How Smoothly Is Your Life Rolling Along? The Wheel of Life Can Change Your Life

Oct 26,2023 9:09 am

-

Decoding the Book of Revelation without the Secret Rapture and 7 Year Tribulation – Professor Walter Veith

Decoding the Book of Revelation without the Secret Rapture and 7 Year Tribulation – Professor Walter Veith

Oct 24,2023 8:40 am

-

Dispensationalism – Zionist Jesuit Futurism – Left Behind Theology

Dispensationalism – Zionist Jesuit Futurism – Left Behind Theology

Oct 23,2023 8:22 am

-

Tom Horn Transhumanism Documentary: Inhuman: The Next and Final Phase of Man is Here

Tom Horn Transhumanism Documentary: Inhuman: The Next and Final Phase of Man is Here

Oct 21,2023 8:28 am

-

EXPOSED !! 20 MILLION DEAD FROM THE JAB, 2.2 BILLION INJURIES – ANALYST ESTIMATES

EXPOSED !! 20 MILLION DEAD FROM THE JAB, 2.2 BILLION INJURIES – ANALYST ESTIMATES

Oct 20,2023 8:21 am

-

Tom Horn, Christian media giant and CEO of Skywatch TV, dies after health struggle

Tom Horn, Christian media giant and CEO of Skywatch TV, dies after health struggle

Oct 14,2023 10:49 am

-

Busted: Flight Aware Changes Turkish Airline TK31 Public Flight Mapping After Being FE Exposed

Busted: Flight Aware Changes Turkish Airline TK31 Public Flight Mapping After Being FE Exposed

Oct 05,2023 6:48 pm

-

From the Fringe: Oxford Scientist John Lennox Warns of The Rise of A.I.

From the Fringe: Oxford Scientist John Lennox Warns of The Rise of A.I.

Oct 05,2023 6:22 am

-

From MSM: Dr. Birx admits to lying about everything all of the time during COVID

From MSM: Dr. Birx admits to lying about everything all of the time during COVID

Sep 30,2023 11:12 am

-

Classic Audio: Gary Allen “None Dare Call It Conspiracy”

Classic Audio: Gary Allen “None Dare Call It Conspiracy”

Sep 29,2023 10:18 am

-

Proving God’s Flat Plane – Flight TK31 From Istanbul, Turkey to Atlanta, GA

Proving God’s Flat Plane – Flight TK31 From Istanbul, Turkey to Atlanta, GA

Sep 26,2023 3:58 pm

-

84 of Chef Politte’s Fast Food Sauce Recipes You Can Make At Home Healthier

84 of Chef Politte’s Fast Food Sauce Recipes You Can Make At Home Healthier

Sep 24,2023 2:20 pm

-

From the Fringe: 2023 ‘End of Mankind’ Prophecy of Moses

From the Fringe: 2023 ‘End of Mankind’ Prophecy of Moses

Sep 23,2023 2:35 pm

-

Predictive Programming Pointing to September 23rd – This Year Perhaps?

Predictive Programming Pointing to September 23rd – This Year Perhaps?

Sep 19,2023 9:00 am

-

160 Countries Have Signed Onto Reducing The World Population To 800 Million By 2030?

160 Countries Have Signed Onto Reducing The World Population To 800 Million By 2030?

Sep 12,2023 5:13 pm

-

Is it True Desani Water by Coca Cola Does Not Freeze?

Is it True Desani Water by Coca Cola Does Not Freeze?

Sep 07,2023 10:29 am

-

Dr. Bill Deagle Dead at 71 – Obituary

Dr. Bill Deagle Dead at 71 – Obituary

Sep 07,2023 9:00 am

-

If the Distance to the Sun is 93 Million Miles, Explain Sun Beam Angles Like This

If the Distance to the Sun is 93 Million Miles, Explain Sun Beam Angles Like This

Sep 06,2023 9:27 am

-

Doctors Took Blood Money Bribes To Get Patient Vaccinations up to 70%

Doctors Took Blood Money Bribes To Get Patient Vaccinations up to 70%

Sep 06,2023 8:08 am

-

From the Fringe: US Military Helicopter Pilot / Engineer on Flat Earth

From the Fringe: US Military Helicopter Pilot / Engineer on Flat Earth

Aug 29,2023 5:29 pm

-

Naturopathic doctor Wil Spencer: Reveals SOLUTIONS to remove vaccine nanocircuitry

Naturopathic doctor Wil Spencer: Reveals SOLUTIONS to remove vaccine nanocircuitry

Aug 26,2023 11:46 am

-

From the Fringe: Dr. Robert Duncan AI V2K Technology and Directed Energy DEW Torture

From the Fringe: Dr. Robert Duncan AI V2K Technology and Directed Energy DEW Torture

Aug 25,2023 8:27 pm

-

From the Fringe: Sacred Frequencies vs The Devil’s Interval That Makes Us Sick

From the Fringe: Sacred Frequencies vs The Devil’s Interval That Makes Us Sick

Aug 24,2023 7:34 pm

-

God has His own Great Reset that Christians expect to start in September

God has His own Great Reset that Christians expect to start in September

Aug 23,2023 10:06 am

-

From the Fringe: They Tried To Kill Bryan Ardis Using Poisoned Bottled Water

From the Fringe: They Tried To Kill Bryan Ardis Using Poisoned Bottled Water

Aug 22,2023 10:04 am

-

Rep. Ron Johnson on Covid: “This was all pre-planned by an elite group of people…”

Rep. Ron Johnson on Covid: “This was all pre-planned by an elite group of people…”

Aug 17,2023 9:25 am

-

Breaking Point – Episode 4 – VACCINES

Breaking Point – Episode 4 – VACCINES

Aug 10,2023 8:35 pm

-

From the Fringe: When Your Early Demise Is Good For Business

From the Fringe: When Your Early Demise Is Good For Business

Aug 10,2023 10:13 am

-

NANOTECH PLANDEMIC — HOPE & TIVON

NANOTECH PLANDEMIC — HOPE & TIVON

Aug 09,2023 9:29 am

-

Greg Reese: IS ANTARCTICA THE KEY TO FLAT EARTH? [2019]

Greg Reese: IS ANTARCTICA THE KEY TO FLAT EARTH? [2019]

Aug 08,2023 9:54 am

-

From the Fringe: Stolen History ‘The Mystery of the World’s Fairs’ Part 3

From the Fringe: Stolen History ‘The Mystery of the World’s Fairs’ Part 3

Jul 29,2023 10:55 am

-

From the Fringe: Our Stolen History – The Destruction of The Old World

From the Fringe: Our Stolen History – The Destruction of The Old World

Jul 27,2023 7:16 pm

-

From the Fringe: The Nuclear Hoax and the 3 Hour Propaganda Movie Oppenheimer

From the Fringe: The Nuclear Hoax and the 3 Hour Propaganda Movie Oppenheimer

Jul 24,2023 2:20 pm

-

Skinny Pie Ideas: Cherry and Apple Pie Filling, No Sugar Added w Pecan Crust

Skinny Pie Ideas: Cherry and Apple Pie Filling, No Sugar Added w Pecan Crust

Jul 21,2023 3:29 pm

-

From The Fringe: A Stranger’s Guide to God’s Earth – 21 Q&A proving a Plane

From The Fringe: A Stranger’s Guide to God’s Earth – 21 Q&A proving a Plane

Jul 19,2023 1:08 pm

-

Delicious Apple & Peach Crisp Recipe Using Stevia and Lucky Leaf Apple Filling

Delicious Apple & Peach Crisp Recipe Using Stevia and Lucky Leaf Apple Filling

Jul 18,2023 3:16 pm

-

BOOM! WE HAVE THEIR NANOTECH GENOCIDAL BEAST PLAN — HOPE & TIVON

BOOM! WE HAVE THEIR NANOTECH GENOCIDAL BEAST PLAN — HOPE & TIVON

Jul 12,2023 9:21 am

-

One World; Two Species; Tartarian DNA

One World; Two Species; Tartarian DNA

Jul 05,2023 12:13 pm

-

Forbidden Electric Technology

Forbidden Electric Technology

Jul 04,2023 12:06 pm

-

Did the Early Church Believe in a Literal Thousand-Year Reign of Christ on Earth?

Did the Early Church Believe in a Literal Thousand-Year Reign of Christ on Earth?

Jun 30,2023 9:12 am

-

How your WiFi Router Helps AI Read your Mind & Use Your Thoughts to pretend to be you.

How your WiFi Router Helps AI Read your Mind & Use Your Thoughts to pretend to be you.

Jun 27,2023 2:44 pm

-

Midnight Ride Special: Tartaria and the 1000 Year Reign

Midnight Ride Special: Tartaria and the 1000 Year Reign

Jun 26,2023 9:26 pm

-

THEY’RE FEEDING US TOXIC SLUDGE — Diane Kazer

THEY’RE FEEDING US TOXIC SLUDGE — Diane Kazer

Jun 25,2023 8:07 am

-

‘Black Mirror’ Season 6 Released June 15, Episode Descriptions

‘Black Mirror’ Season 6 Released June 15, Episode Descriptions

Jun 21,2023 8:54 am

-

COVIDLAND 1) The Lockdown 2) The Mask 3) The Shot

COVIDLAND 1) The Lockdown 2) The Mask 3) The Shot

Jun 18,2023 1:55 pm

-

Why is questioning the shape of the plane(t) a psyop? Veritas Radio

Why is questioning the shape of the plane(t) a psyop? Veritas Radio

Jun 13,2023 9:11 am

-

‘Final Days’ Worldwide Premiere

‘Final Days’ Worldwide Premiere

Jun 06,2023 2:36 pm

-

The Edge AM & Tim Cohen: Antichrist And A Cup Of Tea

The Edge AM & Tim Cohen: Antichrist And A Cup Of Tea

Jun 04,2023 1:54 pm

-

Plandemic 3 – The Great Awakening

Plandemic 3 – The Great Awakening

Jun 04,2023 10:38 am

-

Guideline How To Buy Epic Cash

Guideline How To Buy Epic Cash

May 30,2023 12:08 pm

-

Learn the Truth About Land Ownership in America

Learn the Truth About Land Ownership in America

May 27,2023 11:07 am

-

David Martin Exposes Timeline of Biggest Democide in Recorded History

David Martin Exposes Timeline of Biggest Democide in Recorded History

May 27,2023 10:48 am

-

Noise of Thunder Radio Weekly Feed

Noise of Thunder Radio Weekly Feed

May 25,2023 10:26 am

-

The Cloward-Piven Strategy – Greg Reese

The Cloward-Piven Strategy – Greg Reese

May 20,2023 4:54 pm

-

Updated 05-16-23 – How Much Food Can You Grow in a 10 X 10 Grow Tent or Extra Bedroom?

Updated 05-16-23 – How Much Food Can You Grow in a 10 X 10 Grow Tent or Extra Bedroom?

May 16,2023 9:00 am

-

Iron Republic by Richard Jameson Morgan | Florida Magazine January 1902| As read by Nathan Stolpman

Iron Republic by Richard Jameson Morgan | Florida Magazine January 1902| As read by Nathan Stolpman

May 11,2023 8:49 pm

-

SPACE WOO — DAVID WEISS & JERAN CAMPANELLA on SGT Report

SPACE WOO — DAVID WEISS & JERAN CAMPANELLA on SGT Report

May 10,2023 9:12 am

-

Thermographic Imaging Shows Massive Blood Clots in the Asymptomatic Vaxxed

Thermographic Imaging Shows Massive Blood Clots in the Asymptomatic Vaxxed

May 06,2023 4:17 pm

-

Beyond The Reset – A short film about our not too distant grim future

Beyond The Reset – A short film about our not too distant grim future

Apr 17,2023 6:47 pm

-

Greg Reese: How The Banks Work And Why They Are Collapsing

Greg Reese: How The Banks Work And Why They Are Collapsing

Apr 08,2023 3:31 pm

-

Greg Reese: Are American Farmers Injecting Livestock with mRNA Shots?

Greg Reese: Are American Farmers Injecting Livestock with mRNA Shots?

Apr 06,2023 12:45 pm

-

Flat Earth….a true story…

Flat Earth….a true story…

Apr 02,2023 12:02 pm

-

Documentary: The Shadow State. By The Epoch Times

Documentary: The Shadow State. By The Epoch Times

Mar 29,2023 9:28 am

-

Tucker Carlson Today – Sudden Death Epidemic! – A Must See Video

Tucker Carlson Today – Sudden Death Epidemic! – A Must See Video

Feb 25,2023 8:52 pm

-

IN MEMORIAM TO DR. MICHAEL HEISER

IN MEMORIAM TO DR. MICHAEL HEISER

Feb 22,2023 7:01 pm

-

Egg Conspiracy: A Brand of Feed Stops Chickens From Laying Eggs?

Egg Conspiracy: A Brand of Feed Stops Chickens From Laying Eggs?

Feb 02,2023 8:40 am

-

WEF Wants Ukraine as the Model for UN Agenda 2030 Great Reset Smart City

WEF Wants Ukraine as the Model for UN Agenda 2030 Great Reset Smart City

Jan 22,2023 3:24 pm

-

MUST WATCH Dr Ardis and Mike Adams Break New Ground: Clots, Venom, MORE

MUST WATCH Dr Ardis and Mike Adams Break New Ground: Clots, Venom, MORE

Jan 17,2023 9:30 pm

-

Russian Pianist Gamazda – When You Know All The Piano Lessons Paid Off

Russian Pianist Gamazda – When You Know All The Piano Lessons Paid Off

Jan 16,2023 1:35 pm

-

Protect Yourself From Stolen Mailed Check Washers

Protect Yourself From Stolen Mailed Check Washers

Jan 14,2023 1:20 pm

-

Medvedev Issues Cryptic Message about Restraining the Antichrist

Medvedev Issues Cryptic Message about Restraining the Antichrist

Jan 13,2023 12:11 pm

-

Academic explains how future humans could become ‘part organic, part mechanic cyborgs’

Academic explains how future humans could become ‘part organic, part mechanic cyborgs’

Jan 08,2023 10:29 am

-

Tom Friess Exposes The Global Vatican To Comatose Protestant Americans

Tom Friess Exposes The Global Vatican To Comatose Protestant Americans

Dec 27,2022 9:27 am

-

Disturbing Details About Phone Tracking in 2022 – The Complete Report

Disturbing Details About Phone Tracking in 2022 – The Complete Report

Dec 07,2022 4:05 pm

-

Inviting Generational Curses Into Your Life

Inviting Generational Curses Into Your Life

Dec 06,2022 9:58 am

-

Never Before Seen Photos of Beyond The Ice Wall in Antarctica – Robert Falcon Scott 1912

Never Before Seen Photos of Beyond The Ice Wall in Antarctica – Robert Falcon Scott 1912

Dec 04,2022 10:45 am

-

Dr. Ana Mihalcea: Nanotech in Injections & Quantum Physics, Detoxing

Dr. Ana Mihalcea: Nanotech in Injections & Quantum Physics, Detoxing

Nov 28,2022 4:27 pm

-

World Premiere: Died Suddenly

World Premiere: Died Suddenly

Nov 22,2022 8:50 am

-

Demons – documentary film with Dr. Michael S. Heiser

Demons – documentary film with Dr. Michael S. Heiser

Nov 17,2022 11:36 am

-

Epic Economist: 20 Items That Are Impossible To Find At Grocery Stores Right Now

Epic Economist: 20 Items That Are Impossible To Find At Grocery Stores Right Now

Nov 14,2022 1:15 pm

-

Dr. Lee Merritt & Karen Kingston – It’s All Parasites: Cancer, Vaccines, Remedies

Dr. Lee Merritt & Karen Kingston – It’s All Parasites: Cancer, Vaccines, Remedies

Nov 10,2022 12:27 pm

-

Ezekiel Diet Blog Site Under Construction

Ezekiel Diet Blog Site Under Construction

Nov 05,2022 1:22 pm

-

Commentary on the Key Points and Secrets of The Ezekiel Diet

Commentary on the Key Points and Secrets of The Ezekiel Diet

Nov 05,2022 10:15 am

-

Ben Armstrong: AMERICA in the Book of Revelation and End Times destruction

Ben Armstrong: AMERICA in the Book of Revelation and End Times destruction

Oct 13,2022 11:04 am

-

Financial cycles analyst lays out KEY TIMING WINDOW for catastrophic market crash

Financial cycles analyst lays out KEY TIMING WINDOW for catastrophic market crash

Oct 04,2022 7:34 pm

-

History’s Coming Climax & the Millennium by Professor Walter Veith

History’s Coming Climax & the Millennium by Professor Walter Veith

Sep 29,2022 8:33 am

-

Susan Smith Jones, PhD: Weight Loss Made Easy on The Power Hour

Susan Smith Jones, PhD: Weight Loss Made Easy on The Power Hour

Sep 06,2022 8:43 am

-

My Cold or Flu Protocol

My Cold or Flu Protocol

Jul 18,2022 12:07 pm

-

The Third Temple – Professor Walter Veith

The Third Temple – Professor Walter Veith

Jul 03,2022 12:06 pm

-

Bonhoeffer‘s Theory of Stupidity

Bonhoeffer‘s Theory of Stupidity

Jun 06,2022 3:38 pm

-

Review: Public Rec’s All Day Every Day $108 Pants – Style & Comfort Like No Other

Review: Public Rec’s All Day Every Day $108 Pants – Style & Comfort Like No Other

Jun 02,2022 5:40 pm

-

Living in the Opening Scenes of a Surreal 3D Disaster Movie

Living in the Opening Scenes of a Surreal 3D Disaster Movie

May 04,2022 7:00 am

-

2022 to 2030 Trends Forecast – Ezekiel Diet Files

2022 to 2030 Trends Forecast – Ezekiel Diet Files

May 03,2022 1:04 pm

-

Walmart Is Selling Ezekiel Bread from Food for Life

Walmart Is Selling Ezekiel Bread from Food for Life

Mar 22,2022 8:43 am

-

Meal Testing a 12+ Year Old Bag of Vigo Black Beans & Rice Dinner

Meal Testing a 12+ Year Old Bag of Vigo Black Beans & Rice Dinner

Feb 03,2022 11:19 am

-

Easy Creamy Mushroom Sauce | Chef-Jean Pierre

Easy Creamy Mushroom Sauce | Chef-Jean Pierre

Jan 13,2022 5:09 pm

-

Emergency update: Biden’s promised “winter of severe illness and death” is coming true,

Emergency update: Biden’s promised “winter of severe illness and death” is coming true,

Dec 20,2021 9:11 am

-

Simple vitamin D supplementation could halt covid pandemic, research finds

Simple vitamin D supplementation could halt covid pandemic, research finds

Dec 13,2021 1:00 pm

-

Only TRUE Believers Can See The Signs

Only TRUE Believers Can See The Signs

Nov 23,2021 11:59 am

-

Why Michelangelo Painted Ezekiel on the Sistine Chapel Ceiling So Muscular

Why Michelangelo Painted Ezekiel on the Sistine Chapel Ceiling So Muscular

Nov 22,2021 5:03 pm

-

The Columbus Moment 2022 – Ark To Paradise – Fleeing Protestant Persecution

The Columbus Moment 2022 – Ark To Paradise – Fleeing Protestant Persecution

Nov 20,2021 12:21 pm

-

Do we Lose our Salvation if our DNA is Changed? 11/12/2021

Do we Lose our Salvation if our DNA is Changed? 11/12/2021

Nov 12,2021 9:04 am

-

Russ Dizdar Obituary, Death, Tributes, Cause Of Death, Funeral

Russ Dizdar Obituary, Death, Tributes, Cause Of Death, Funeral

Oct 22,2021 3:03 pm

-

Dr. Chris A. Knobbe verifies processed oils are at the core of nearly all disease

Dr. Chris A. Knobbe verifies processed oils are at the core of nearly all disease

Oct 21,2021 6:35 am

-

Rob Skiba Obituary Dallas, TX, Author Rob Skiba Covid-19 Death

Rob Skiba Obituary Dallas, TX, Author Rob Skiba Covid-19 Death

Oct 19,2021 10:00 am

-

Interview: William Davis MD Author of Wheat Belly

Interview: William Davis MD Author of Wheat Belly

Oct 04,2021 2:01 pm

-

Strawberry Short the Cake Dessert – 175 calorie Thawberries and Reddi Wip Topping

Strawberry Short the Cake Dessert – 175 calorie Thawberries and Reddi Wip Topping

Oct 03,2021 10:00 am

-

Which Fry is the Better Choice: Potato vs. Sweet Potato?

Which Fry is the Better Choice: Potato vs. Sweet Potato?

Oct 03,2021 8:52 am

-

It’s a Pandemic of the Old, Fat, Vaccinated, Sick and Undernourished

It’s a Pandemic of the Old, Fat, Vaccinated, Sick and Undernourished

Sep 27,2021 5:04 pm

-

Hydrogen Peroxide Nebulization and COVID Resolution Impressive Anecdotal Results

Hydrogen Peroxide Nebulization and COVID Resolution Impressive Anecdotal Results

Sep 22,2021 1:31 pm

-

Research Confirms Sweating Detoxifies Dangerous Metals, Petrochemicals

Research Confirms Sweating Detoxifies Dangerous Metals, Petrochemicals

Sep 22,2021 12:30 pm

-

Linus Pauling’s Recommendations for Vitamin C and Lysine

Linus Pauling’s Recommendations for Vitamin C and Lysine

Sep 22,2021 11:11 am

-

Dr. Russell Blaylock – Nutrition and Behavior, the Dangers of Aspartame and MSG on Brain Function

Dr. Russell Blaylock – Nutrition and Behavior, the Dangers of Aspartame and MSG on Brain Function

Sep 17,2021 10:04 am

-

Dr. Mercola discusses Hydrogen Peroxide Nebulization

Dr. Mercola discusses Hydrogen Peroxide Nebulization

Sep 16,2021 2:55 pm

-

Virologists reveal how poor man’s amino acid cure for COVID-19 would abolish need for vaccines

Virologists reveal how poor man’s amino acid cure for COVID-19 would abolish need for vaccines

Sep 14,2021 7:03 pm

-

Getting Your Affairs In Order – Estate Planning

Getting Your Affairs In Order – Estate Planning

Sep 06,2021 2:02 pm

-

Christian Non-Profit TeleMedicine MyFreeDoctor.com – Early MULTI DRUG treatment at home saves lives!

Christian Non-Profit TeleMedicine MyFreeDoctor.com – Early MULTI DRUG treatment at home saves lives!

Aug 25,2021 8:50 am

-

Are you getting enough vitamin D? Low levels linked to compromised immune function

Are you getting enough vitamin D? Low levels linked to compromised immune function

Jul 30,2021 1:49 pm

-

The Mark And The Number Of His Name The Whole Truth – Walter Veith

The Mark And The Number Of His Name The Whole Truth – Walter Veith

Jul 26,2021 10:33 am

-

Walter Veith – The Moment Of Crisis

Walter Veith – The Moment Of Crisis

Jul 22,2021 11:47 am

-

Secret Covenant of the Illuminati | New World Order

Secret Covenant of the Illuminati | New World Order

Jul 21,2021 9:52 am

-

Updated Skinny Pumpkin Pie and Skinny Cheesecake Recipe Ideas and Instructions

Updated Skinny Pumpkin Pie and Skinny Cheesecake Recipe Ideas and Instructions

Jul 13,2021 11:16 am

-

The “Junque” People Hoard Until Death and Leave for Estate Sale Firms To Clean Up

The “Junque” People Hoard Until Death and Leave for Estate Sale Firms To Clean Up

Jun 14,2021 9:55 am

-

Electrolyte Imbalance: Conditions & Concerns – Too Much or Too Little Potassium

Electrolyte Imbalance: Conditions & Concerns – Too Much or Too Little Potassium

May 02,2021 8:12 am

-

Eugenics, Fluoride & Vaccines – Neurosurgeon, Dr. Russell Blaylock

Eugenics, Fluoride & Vaccines – Neurosurgeon, Dr. Russell Blaylock

Apr 13,2021 8:47 am

-

Colloidal Silver – The Blue Man Fraud

Colloidal Silver – The Blue Man Fraud

Apr 05,2021 9:05 am

-

Vitamin D deficiency is the primary cause of covid hospitalizations and deaths

Vitamin D deficiency is the primary cause of covid hospitalizations and deaths

Mar 31,2021 9:27 am

-

God’s great reset

God’s great reset

Mar 24,2021 6:13 pm

-

The 10 Best Foods to Boost Nitric Oxide Levels

The 10 Best Foods to Boost Nitric Oxide Levels

Mar 23,2021 5:12 pm

-

Vitamin B6 found to reduce the severity of COVID-19

Vitamin B6 found to reduce the severity of COVID-19

Mar 23,2021 9:02 am

-

Foods That Boost A Slow Metabolism And Repair Metabolic Damage

Foods That Boost A Slow Metabolism And Repair Metabolic Damage

Mar 20,2021 7:15 am

-

Dental Wisdom: Dental Provider Network Discounts verses Dental Insurance

Dental Wisdom: Dental Provider Network Discounts verses Dental Insurance

Mar 15,2021 12:11 pm

-

Fresh Pork Parasites Don’t Like Pepsi! Must See

Fresh Pork Parasites Don’t Like Pepsi! Must See

Mar 10,2021 4:36 pm

-

Stan Johnson: Direct Attack on Christians – 3 Parts

Stan Johnson: Direct Attack on Christians – 3 Parts

Mar 03,2021 11:11 am

-

Virologists Report Poor Man’s Amino Acid Cure for Covid-19 Would Abolish Need for Vaccines

Virologists Report Poor Man’s Amino Acid Cure for Covid-19 Would Abolish Need for Vaccines

Feb 22,2021 3:08 pm

-

Must Know: Satan’s Strategy for Protestants in America

Must Know: Satan’s Strategy for Protestants in America

Feb 21,2021 10:34 am

-

Dr. Luke Prophet on Current Events and Bible Prophecy

Dr. Luke Prophet on Current Events and Bible Prophecy

Feb 17,2021 12:54 pm

-

Baby Boomer discounts you have to ask for. Ask Not Have Not.

Baby Boomer discounts you have to ask for. Ask Not Have Not.

Feb 11,2021 10:39 am

-

How Ashwagandha Works To Control Stress, Anxiety and Cortisol from Trump-be-gone-dha

How Ashwagandha Works To Control Stress, Anxiety and Cortisol from Trump-be-gone-dha

Feb 10,2021 12:50 pm

-

Let me tell you why you are here. You’re being slowly murdered by design.

Let me tell you why you are here. You’re being slowly murdered by design.

Feb 10,2021 9:23 am

-

Seek The LORD While He May Be Found

Seek The LORD While He May Be Found

Feb 09,2021 8:42 am

-

Free Ezekiel Diet Condensed PDF – Pictures, Meals, Desserts, and Secrets

Free Ezekiel Diet Condensed PDF – Pictures, Meals, Desserts, and Secrets

Feb 09,2021 8:17 am

-

Lower your blood sugar and prevent nerve damage linked to diabetes with alpha-lipoic acid

Lower your blood sugar and prevent nerve damage linked to diabetes with alpha-lipoic acid

Feb 09,2021 8:16 am

-

Updated: Making Perfect Shirts Without Spending a Fortune

Updated: Making Perfect Shirts Without Spending a Fortune

Feb 05,2021 11:39 am

-

British legislator calls for widespread vitamin D rollout following 82% reduction in COVID-19 deaths in Spain

British legislator calls for widespread vitamin D rollout following 82% reduction in COVID-19 deaths in Spain

Jan 23,2021 12:10 pm

-

Good News – The astonishing case for optimism and faith

Good News – The astonishing case for optimism and faith

Jan 21,2021 1:25 pm

-

What Are The Benefits of Himalayan Crystal Salt Lamps? Why Should You Use Salt Lamps?

What Are The Benefits of Himalayan Crystal Salt Lamps? Why Should You Use Salt Lamps?

Jan 17,2021 10:12 am

-

30 Easy Ways to Lose Weight Naturally (Backed by Science)

30 Easy Ways to Lose Weight Naturally (Backed by Science)

Jan 12,2021 6:28 am

-

Battling the Enemy: Spiritual Warfare in Weight Loss

Battling the Enemy: Spiritual Warfare in Weight Loss

Jan 08,2021 7:21 am

-

Study: Eating One Bar of Dark Chocolate can Reduce “Excess Body Fat” in One Week

Study: Eating One Bar of Dark Chocolate can Reduce “Excess Body Fat” in One Week

Jan 04,2021 10:15 am

-

The Who and Why Truth Behind the Deceptive Matrix We Live In

The Who and Why Truth Behind the Deceptive Matrix We Live In

Jan 04,2021 10:00 am

-

The Missing Ingredient to Lasting Weight Loss That Secular Programs Just Don’t Get

The Missing Ingredient to Lasting Weight Loss That Secular Programs Just Don’t Get

Jan 04,2021 9:29 am

-

Blessing – and breaking – the very makeup of food

Blessing – and breaking – the very makeup of food

Dec 31,2020 3:08 pm

-

I Am 60 Years Old And This Plant Returned My Vision, Removed Fat From My Liver And Cleansed My Colon

I Am 60 Years Old And This Plant Returned My Vision, Removed Fat From My Liver And Cleansed My Colon

Dec 25,2020 3:20 pm

-

Green tea compounds block key enzyme that allows coronavirus to replicate – study

Green tea compounds block key enzyme that allows coronavirus to replicate – study

Dec 16,2020 8:59 am

-

Organic strawberries can stop the growth of cancer cells – science explains how

Organic strawberries can stop the growth of cancer cells – science explains how

Dec 01,2020 8:35 pm

-

Shared Wisdom: Avoid starting over.

Shared Wisdom: Avoid starting over.

Nov 29,2020 10:17 am

-

Skinny Cheesecake & Graham Cracker Crust Only 77 Calories Per Slice

Skinny Cheesecake & Graham Cracker Crust Only 77 Calories Per Slice

Nov 25,2020 12:56 pm

-

True Food Kitchen Butternut Squash Pie Recipe – Holiday Pie Idea

True Food Kitchen Butternut Squash Pie Recipe – Holiday Pie Idea

Nov 25,2020 9:01 am

-

Skinny Pie and Healthy Dessert Idea Index

Skinny Pie and Healthy Dessert Idea Index

Nov 25,2020 6:35 am

-

Tom Horn: The Evil Gene and Lucifer Effect

Tom Horn: The Evil Gene and Lucifer Effect

Oct 26,2020 10:48 am

-

Next Hoax – Alien Invasion Fast Tracks Global Religion – Dr. Steven Greer, Tom Horn, Cris Putnam

Next Hoax – Alien Invasion Fast Tracks Global Religion – Dr. Steven Greer, Tom Horn, Cris Putnam

Oct 25,2020 8:21 am

-

Do we get a reformatting memory wipe in heaven? Yes.

Do we get a reformatting memory wipe in heaven? Yes.

Oct 08,2020 11:01 am

-

Green tea, zinc proving BETTER than hydroxychloroquine at fighting coronavirus?

Green tea, zinc proving BETTER than hydroxychloroquine at fighting coronavirus?

Oct 03,2020 8:54 am

-

30 Day Emergency Food Supply for 4 from Mart and Dollar Stores

30 Day Emergency Food Supply for 4 from Mart and Dollar Stores

Sep 29,2020 6:39 am

-

Now when these things begin to happen, look up and lift up your heads, because your redemption draws near.

Now when these things begin to happen, look up and lift up your heads, because your redemption draws near.

Sep 25,2020 8:43 am

-

Financial Umbrella: Put a Missionary on the Payroll

Financial Umbrella: Put a Missionary on the Payroll

Sep 07,2020 6:06 am

-

Perfect Example of How Words Spoken Out Loud Are Programming in this Matrix

Perfect Example of How Words Spoken Out Loud Are Programming in this Matrix

Aug 27,2020 2:54 pm

-

Better brain health | DW Documentary

Better brain health | DW Documentary

Aug 02,2020 2:02 pm

-

How To Prove To Yourself We Live In A Simulation Programmed By Prayer

How To Prove To Yourself We Live In A Simulation Programmed By Prayer

Jul 30,2020 11:38 am

-

Top 10 fruits doused in toxic chemicals

Top 10 fruits doused in toxic chemicals

Jul 21,2020 6:29 am

-

‘Black Injustice In The Old South’ Movies – How Hollywood Helped Foment Race War In America

‘Black Injustice In The Old South’ Movies – How Hollywood Helped Foment Race War In America

Jun 12,2020 9:33 am

-

‘Upload’ Is the Latest Predictive Programming Depicting the Afterlife as Simulation – Hard Drive Selfie

‘Upload’ Is the Latest Predictive Programming Depicting the Afterlife as Simulation – Hard Drive Selfie

May 31,2020 5:57 pm

-

THE MOST ENLIGHTENING CONVERSATION ON DEMONOLOGY EVER!

THE MOST ENLIGHTENING CONVERSATION ON DEMONOLOGY EVER!

May 19,2020 5:17 pm

-

Take Back Your Mind, Energy Levels and Eliminate Dry Skin and Wiry Hair

Take Back Your Mind, Energy Levels and Eliminate Dry Skin and Wiry Hair

May 08,2020 12:37 pm

-

Book: Behind the Dictators – The strategy to manually fulfill the futurist Antichrist thesis

Book: Behind the Dictators – The strategy to manually fulfill the futurist Antichrist thesis

Apr 29,2020 9:56 am

-

2020 to 2022 Stan Johnson on Omegaman 04/17/2020

2020 to 2022 Stan Johnson on Omegaman 04/17/2020

Apr 18,2020 9:55 am

-

MISS THE MARK: Don’t take the Mark of the Beast – Stan Johnson Prophecy Club

MISS THE MARK: Don’t take the Mark of the Beast – Stan Johnson Prophecy Club

Apr 17,2020 8:12 pm

-

10 Health Benefits of Grapefruits

10 Health Benefits of Grapefruits

Apr 16,2020 9:33 pm

-

Where is all this going? The Mark of the Beast.

Where is all this going? The Mark of the Beast.

Apr 12,2020 7:47 pm

-

America in Bible Prophecy – Jonathan Gray

America in Bible Prophecy – Jonathan Gray

Mar 29,2020 10:18 am

-

$550 Whole House Fluoride, Chlorine, Lead, Contaminant Filter from Lowe’s or Home Depot

$550 Whole House Fluoride, Chlorine, Lead, Contaminant Filter from Lowe’s or Home Depot

Mar 28,2020 9:03 pm

-

Psalm 91

Psalm 91

Mar 26,2020 10:19 am

-

Is Kirkland Water From Costco Bad For You?

Is Kirkland Water From Costco Bad For You?

Feb 29,2020 6:26 am

-

DEPOPULATION: Death in America Is Alive & Well

DEPOPULATION: Death in America Is Alive & Well

Feb 24,2020 8:23 am

-

Prayer, Driving and a Coronavirus Reminder

Prayer, Driving and a Coronavirus Reminder

Feb 11,2020 1:49 pm

-

Portable Water Purification – Why, How, and Where – Boiling, Clorox, and Portable Filters

Portable Water Purification – Why, How, and Where – Boiling, Clorox, and Portable Filters

Feb 01,2020 6:00 am

-

The Scheme to Double Lifetime Revenue on Every American

The Scheme to Double Lifetime Revenue on Every American

Jan 14,2020 9:42 am

-

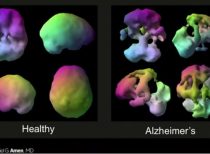

You are in a WAR for the Health of Your Brain – Daniel Amen M.D.

You are in a WAR for the Health of Your Brain – Daniel Amen M.D.

Jan 06,2020 2:45 pm

-

Free Ezekiel Diet Fresh Food Grocery List – with Calorie Count & Serving Sizes

Free Ezekiel Diet Fresh Food Grocery List – with Calorie Count & Serving Sizes

Jan 06,2020 9:05 am

-

What happens in your body within one hour after you drink a Coca-Cola

What happens in your body within one hour after you drink a Coca-Cola

Jan 06,2020 6:44 am

-

Fried Food May Be Killing You, a New Study Says.

Fried Food May Be Killing You, a New Study Says.

Dec 27,2019 11:30 am

-

The Possibility: 4K Ultra High Definition Smart TVs in Place of Static Art

The Possibility: 4K Ultra High Definition Smart TVs in Place of Static Art

Dec 23,2019 8:33 am

-

The Problem with Stevia – Dr. Berg

The Problem with Stevia – Dr. Berg

Dec 10,2019 1:23 pm

-

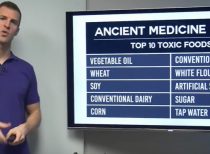

Top 10 Toxic Foods and Top 10 Healing Foods | Dr. Josh Axe

Top 10 Toxic Foods and Top 10 Healing Foods | Dr. Josh Axe

Dec 01,2019 12:03 pm

-

“The Inquisition Was Particularly Hard On Us.” Tour Guide in Cartagena, Columbia

“The Inquisition Was Particularly Hard On Us.” Tour Guide in Cartagena, Columbia

Nov 20,2019 2:53 pm

-

How To Lose Belly Fat Naturally Without Exercise – Dr. Stan Ekberg

How To Lose Belly Fat Naturally Without Exercise – Dr. Stan Ekberg

Oct 20,2019 1:34 pm

-

Are Fast Food Giants Struggling Because Many Are Waking Up To How Fast Food Is Making Them Sick, Tired & Fat?

Are Fast Food Giants Struggling Because Many Are Waking Up To How Fast Food Is Making Them Sick, Tired & Fat?

Oct 18,2019 1:38 pm

-

Fasting vs. Eating Less: What’s the Difference? (Science of Fasting)

Fasting vs. Eating Less: What’s the Difference? (Science of Fasting)

Oct 18,2019 11:33 am

-

Man’s health radically transforms after just 30 days off sugar and alcohol

Man’s health radically transforms after just 30 days off sugar and alcohol

Oct 18,2019 8:27 am

-

Farmed Salmon — One of the Most Toxic Foods in the World?

Farmed Salmon — One of the Most Toxic Foods in the World?

Sep 24,2019 3:39 pm

-

Did She Turn 2 Simple Ingredients Into a Cure For Cancer? Dr. Johanna Budwig

Did She Turn 2 Simple Ingredients Into a Cure For Cancer? Dr. Johanna Budwig

Sep 24,2019 9:31 am

-

GMO Food — It’s Worse Than We Thought – Dr. Russell Blaylock

GMO Food — It’s Worse Than We Thought – Dr. Russell Blaylock

Sep 24,2019 6:21 am

-

Stunned researchers discover walking dramatically boosts blood flow to the brain, boosting cognitive function

Stunned researchers discover walking dramatically boosts blood flow to the brain, boosting cognitive function

Sep 24,2019 6:00 am

-

How to Lower Cortisol – Dr. Berg

How to Lower Cortisol – Dr. Berg

Sep 11,2019 9:40 pm

-

Star Signs Converging Now Predict the Return of Jesus – Jonathan Gray Archeologist

Star Signs Converging Now Predict the Return of Jesus – Jonathan Gray Archeologist

Sep 10,2019 9:33 am

-

How Hormones Influence You and Your Mind

How Hormones Influence You and Your Mind

Sep 09,2019 5:59 pm

-

Long life depends on this: Gary Wenk TedX Talk

Long life depends on this: Gary Wenk TedX Talk

Sep 09,2019 3:44 pm

-

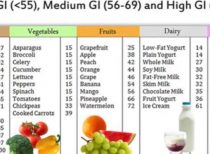

The Carbs that are Worse than Sugar

The Carbs that are Worse than Sugar

Sep 06,2019 12:35 pm

-

Dark Chocolate Hack To Reduce Sugar & Insulin Spikes

Dark Chocolate Hack To Reduce Sugar & Insulin Spikes

Sep 06,2019 10:51 am

-

The Average Physical Condition of 4,100 Passengers on a Cruise Ship

The Average Physical Condition of 4,100 Passengers on a Cruise Ship

Sep 02,2019 8:40 am

-

15 Intermittent Fasting Mistakes That Make You Gain Weight

15 Intermittent Fasting Mistakes That Make You Gain Weight

Sep 01,2019 4:53 pm

-

Are You Salt Sensitive or Potassium Deficient

Are You Salt Sensitive or Potassium Deficient

Sep 01,2019 12:17 pm

-

FASTING AWAY DIABESITY? Ft. Jason Fung, Nephrologist & Best-selling author

FASTING AWAY DIABESITY? Ft. Jason Fung, Nephrologist & Best-selling author

Sep 01,2019 11:30 am

-

How Corporations Ruined Food (Food Industry Documentary) – Real Stories

How Corporations Ruined Food (Food Industry Documentary) – Real Stories

Aug 11,2019 10:56 am

-

How Much Coffee Should I Drink Daily?

How Much Coffee Should I Drink Daily?

Jul 22,2019 6:33 am

-

6 Household Spices that Destroy Cancer Cells, Prevent Heart Attacks & Rebuilds Our Gut

6 Household Spices that Destroy Cancer Cells, Prevent Heart Attacks & Rebuilds Our Gut

Jul 21,2019 8:20 am

-

Powerful Antioxidants to Longevity

Powerful Antioxidants to Longevity

Jul 20,2019 12:57 pm

-

The hormone balance plan – The Hormone Diet – by Dr. Natasha Turner

The hormone balance plan – The Hormone Diet – by Dr. Natasha Turner

Jul 16,2019 6:58 am

-

Science Says 1 Minute of this Exercise is = to 45 min. of Jogging

Science Says 1 Minute of this Exercise is = to 45 min. of Jogging

Jul 05,2019 10:49 am

-

Stop Eating Poison – John McDougall MD

Stop Eating Poison – John McDougall MD

Jun 29,2019 10:34 am

-

Simple Keto Meal Plan For The Week – Burn Fat and Lose Weight

Simple Keto Meal Plan For The Week – Burn Fat and Lose Weight

Jun 24,2019 6:54 pm

-

10 Best Ways To Avoid Weight Gain On A Cruise

10 Best Ways To Avoid Weight Gain On A Cruise

Jun 24,2019 4:30 pm

-

How To Measure Your Depth & What Is Average Depth?

How To Measure Your Depth & What Is Average Depth?

Jun 22,2019 8:22 pm

-

Costco Roasted Organic Chicken Wings & Vegetables

Costco Roasted Organic Chicken Wings & Vegetables

Jun 22,2019 7:04 pm

-

7 Cooking Oils Explained At Costco..The Good, Bad & Toxic!

7 Cooking Oils Explained At Costco..The Good, Bad & Toxic!

Jun 21,2019 12:08 pm

-

EZ Diet Meal Idea – Roasted Chicken & Vegetables in 30 Minutes

EZ Diet Meal Idea – Roasted Chicken & Vegetables in 30 Minutes

Jun 02,2019 8:54 pm

-

Raspberries prevent cancer, diabetes, obesity, and arthritis!

Raspberries prevent cancer, diabetes, obesity, and arthritis!

May 31,2019 12:23 pm

-

What Nutrition Experts Eat On Vacation

What Nutrition Experts Eat On Vacation

May 31,2019 10:18 am

-

1/2 BBQ Chicken, Fries, Cole Slaw = 4,000 mg Sodium and requires 12,000 mg Potassium to Balance

1/2 BBQ Chicken, Fries, Cole Slaw = 4,000 mg Sodium and requires 12,000 mg Potassium to Balance

May 31,2019 9:48 am

-

The Benefits of Vitamin C With Rose Hips for Skin Tone

The Benefits of Vitamin C With Rose Hips for Skin Tone

May 31,2019 9:01 am

-

What the Dairy Industry Doesn’t Want You to Know – Neal Barnard MD

What the Dairy Industry Doesn’t Want You to Know – Neal Barnard MD

May 24,2019 9:51 am

-

Why Chinese cinnamon should be part of your weight loss plans

Why Chinese cinnamon should be part of your weight loss plans

May 21,2019 9:53 pm

-

Worried about your blood sugar? Experts recommend checking your magnesium levels

Worried about your blood sugar? Experts recommend checking your magnesium levels

May 21,2019 7:03 am

-

Top five weight loss detox plans

Top five weight loss detox plans

May 21,2019 6:38 am

-

HISTORY OF RELIGION (Part 1): PAGANS, NIMROD, & BABYLON

HISTORY OF RELIGION (Part 1): PAGANS, NIMROD, & BABYLON

May 19,2019 5:31 pm

-

Scientists explore chestnut flower for its anti-obesity properties

Scientists explore chestnut flower for its anti-obesity properties

May 16,2019 8:31 am

-

Tongbi-san can be used to treat obesity,

Tongbi-san can be used to treat obesity,

May 12,2019 8:32 am

-

Sweet superfood: The 6 health benefits of nutrient-rich sweet potatoes

Sweet superfood: The 6 health benefits of nutrient-rich sweet potatoes

May 11,2019 3:45 pm

-

Eating to beat depression: Foods that improve your gut health also improve your mental health

Eating to beat depression: Foods that improve your gut health also improve your mental health

May 11,2019 3:40 pm

-

Overweight in the Workplace (HBO: The Weight of the Nation)

Overweight in the Workplace (HBO: The Weight of the Nation)

Apr 24,2019 7:04 pm

-